April 26, 1952

(courtesy of Winfried Stiffel)

NEWSPAPER REVIEWS

La Nazione Italiana (April 26, 1952)

La Nazione Italiana (April 27, 1952)

Avanti (April 27, 1952)

Oggi (May 8, 1952)

La Nazione Italiana

April 26, 1952

(courtesy of Winfried Stiffel)

XV Maggio Musicale Fiorentino opens tonight with “Armida”

Ministers, ambassadors, and figures of international politics and culture participate today in the after-show reception at the Palazzo Vecchio

Tonight, at 9 PM, the Teatro Comunale will reopen for the inauguration of the “XV Maggio Musicale Fiorentino” with Rossini’s “Armida.” The opera, conducted by Tullio Serafin, will feature as main interpreters: Maria Meneghini Callas in the principal role, Francesco Albanese, Mario Filippeschi, Gianni Raimondi, Antonio Salvarezza, and Alessandro Ziliani. The staging, set design and costumes are by Alberto Savinio; choreography by Léonide Massine; the chorus master is Andrea Morosini; stage production by Piero Caliterna; dancers: René Bon, Janine Charrat, Milorad Miskovich, Wladimir Oukhomsky, Claire Sombert, Hélène Traïline, Carlo Faraboni, Geneviève Lespagnol and Boris Traïline.

For the occasion, this afternoon at 6:30 PM, the Honorable Mayor Giorgio La Pira will offer a grand reception at Palazzo Vecchio for the ministers, ambassadors, artists, politicians and international cultural figures who have gathered in our city.

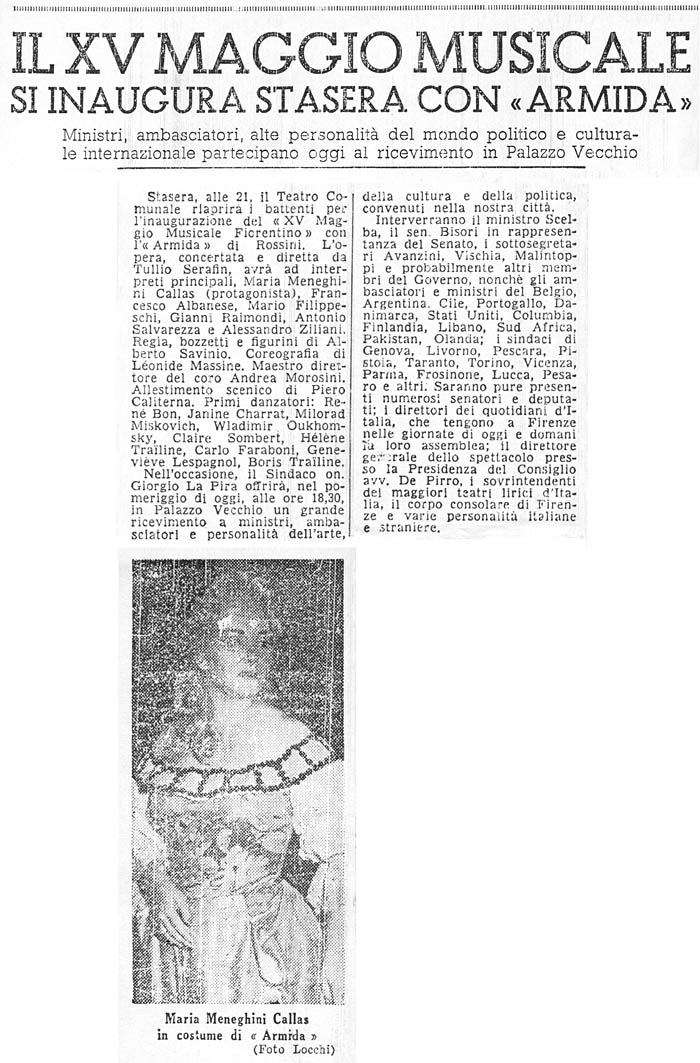

This will include Minister Scelba, Senator Bisori as the representative of the Senate, Undersecretaries Avanzini, Vischia, Malintoppi and other members of the government; also ambassadors and ministers of Belgium, Argentina, Chile, Portugal, Denmark, United States of America, Colombia, Finland, Lebanon, South Africa, Pakistan and Holland; Mayors of Genoa, Livorno, Pescara, Pistoia, Taranto, Torino, Vicenza, Parma, Frosinone, Lucca, Pesaro, and other cities. Many congressmen and deputies, directors of Italian newspapers, whose meeting is being held in Florence these days, will also be present, along with the general director of performance from the Council Presidency, directors of major Italian lyrical theaters, the Consular Body of Florence and various Italian and foreign figures.Maria Meneghini Callas in Armida’s costume (photo by Locchi)

La Nazione Italiana

April 27, 1952

(courtesy of Monica Wiards)

Florence and Its Spring

Successful baptism of the 15th “Maggio” with Gioacchino Rossini’s “Armida”First of all, it is a grand show of modern taste that does not exhume nor copy anything. It is also an excellent performance. Rossini had composed “Armida” for Barbaja, in Naples; and Barbaja was an impresario who liked to do things in grand style: beautiful, magnificent scenes, lavish dances, lighting and stage machinery at will. At that time, there was no director and the stage direction was given to the conductor — very often the composer himself — together with the choreographer. Thus, the concept of the music was not detached from that of the show as it is today, and now and then one took over the other, to great discomfort of pure musicians – who spoke of “operas more to be seen than heard” — or the fans of stage direction and dance.

It is strange how, half a century before Verdi at the time of “Aida,” Rossini was also accused of “Germanizing” and bastardizing the bel canto in “Armida.” Apart from the “German” issue, maybe the accusers were not wrong, because in “Armida,” Rossini did what he was specifically asked to do, that is, he composed stage drama music. And, probably knowing nothing at all about the “Intermedio” or the “Opéra ballet” by another “Armida” composer, Lulli, Rossini understood that he needed to create a show in which no element could overshadow another; the singing only had to complete the stage action, and the dances had to balance and almost serve as a counterweight for the tragic adventures of the Sorceress and the Crusader. That is why Rossini probably found more room for the experimental — at the time of “Armida,” he was only twenty-five years old — and, attracted to the exotic splendor of the plot and the setting, he searched for a music more refined and solid than the harmonic style in vogue at the time, a richer and more diverse instrumental texture, in short, a local color that could not be fully appreciated because the exoticism and musical folklore were not yet in fashion, a style that, to the prudish ears of listeners of the early nineteen century, must have sounded barbarian and “Germanized.”

And there are passages where we recognize the true, undeniable musician, strokes of a pure, genuine Rossini: the beautiful duet of the First Act, some passages taken from “Mosè,” Armida’s Second Act aria, where virtuosity is musically necessary and even irreplaceable. Yet, even during the many inexpressive and futile passages, the composer remains a musician of large and secure breath, a skilled musician with an unerring, sharp eye.

But the documentary and historical value of the piece — maybe even more important for history of the 19th century melodrama than for Rossini’s personal history — means more to the experts than to the general audience. Let us go back to the show itself. Alberto Savinio was in charge of the staging and the direction. Both are most intelligent and refined, suitable not only for the fable of Armida but also for what Armida suggested to Rossini’s music. Particular attention is given to the First Act, set in a uniform gray tone: backdrops, the crusaders’ tents and costumes; even their banners, helmets and wigs. Then, on top of all that quiet and warm gray, only a few costumes were in vivid colors: the train of the afflicted and deceitful Armida. The scenic effect was flawless. The Second Act was prepared with great care and an almost cinematographic visual rhythm: the Hell scene, with its demons and Astarotte, slowly turning into Armida’s enchanted palace. And a long dance scene has been composed by Léonide Massine — the great Massine, choreographer of Diaghilev.

Massine is an extraordinary choreographer. His foremost quality is the enormous richness of language: combinations, steps and poses follow one after another with seemingly endless imagination; a continuous change and transformation in the style of the great Massinian choreographers. The inspired stances of a popular Spanish dance go beyond sophisticated symbolic evocations of an apparently baroque Greece with spontaneity; the whole dance seems to be improvised freely on the score.

The performance, in care of Tullio Serafin and a train of most worthy performers, left an excellent impression in regard to the music and singing. Maria Meneghini Callas sang as convincingly as a refined actress is able to: regal, passionate, desperate, she measured her bearings with fascinating sensibility and rhythm. Vocally, she dominated the whole opera, from the very beginning to the very end: in long singing outpourings, in sparkling bravura cabalettas, in the more dramatic and agitated passages, she found the tone that the music demanded, creating a feminine and touching vocal drama. Francesco Albanese sang Rinaldo with excellent means, color, persuasion, attentive musicality and vocal intelligence. He lacked, maybe, more coherent and measured acting.

The other male characters were all performed by high-level singers, those who are among the best in present lyrical Italian theatre: Filippeschi played Gernando with beautiful diction, vigorous agitation, and a remarkable expressive force. Ziliani sang the dignified and stern part of Goffredo di Buglione with the noble majesty that the role demands. Antonio Salvarezza and Gianni Raimondi interpreted the parts of Carlo and Ubaldo, the two Paladins who went to release the hero from Armida’s loving traps, with great vocal clarity and immediate sensibility. Marco Stefanoni and Mario Frosini, who played the “oriental” parts of Astarotte and Idraote, were excellent, too.

The ballet company of Janine Charrat, an important name of the new French school, fully completed their neither easy nor light task. Charrat herself, Miskovic, Helen Trailine, René Bon, Oukhtomsky, Claire Sombert, Carletto Faraboni, Boris Trailine and Geneviève Lespagnol danced with technical dexterity and expressive liveliness. They fulfilled the important requirements of a particularly demanding choreography.

Andrea Morosini instructed and lead the chorus with his usual expertise and Olympic calmness.

The whole complex show was under the direction of Tullio Serafin. With the supreme wisdom and great intuition of a born and experienced man of theater, he continuously showed his solid yet elastic, intelligent and loving dominance over the stage, orchestra, and show.Gualtiero Frangini

The show was a very warm success. First, a big applause for Tullio Serafin after the overture; then the finest and most virtuoso arias were applauded during the performance itself. There were numerous calls at the end of every act, and Savinio’s staging and the choreography were very favorably received, too.

Avanti

April 27, 1952

(courtesy of Winfried Stiffel)

The Fifteenth Maggio Musicale Fiorentino Opens With “Armida”

Florence, 26 April 1952. — The “Maggio Musicale Fiorentino” festival opened tonight at the Teatro Comunale with a homage to Rossini. In fact, as many as six operas are represented in the repertory to celebrate the greatness of this unique composer who can be said to have brought to a close the glory of Italian music in the nineteenth century. “Armida” was chosen to open this series, an opera in which one hears a distillation of Rossini as composer of “opera seria”. A distillation, of course, with its boundaries of richness and paucity, of worth and inadequacy. In short, it can be said that the opinion that Beethoven once expressed to our composer (“do not attempt anything other than writing comic operas: wishing to succeed in another musical genre would be going against your own nature”) had not been altogether inaccurate, even though it seemed excessively harsh, as it appeared to disregard numerous pages from such operas as “Tancredi”, “Mosè”, “Otello”, and even “Armida” itself.

However, one must admit that Rossini’s merits in the “opera seria” genre appear to be episodic, that is, they reveal themselves in passages of felicitous lyrical expansion, as well as psychological intuition, but they are unable to coalesce into an integrated dramatic construction of situations and characters. In short, the marvelous flair for the theater that in the “opera buffa” genre distinguishes this musician above all other Italian opera composers, with the exception of Verdi, is without a doubt lacking in an opera such as “Armida”.

Its characters appear schematized in their feelings and seem to bask in their respective passions; Rossini appears to lose himself in an introspective effort and in the expressive search for intimate drama. This leads him to some extremely intense passages, but at the same time causes him to lose the feeling for the scenic narrative and, with this, also the zest for the spectacle.

“Armida” was composed and performed at Naples in 1817. The subject at that time already had several illustrious antecedents: it should suffice to mention Lully and Gluck, who wrote two very interesting works about Rolando’s adventures. However, Rossini did not believe in emulating the past and repeating the style and atmosphere of eighteenth century opera. Hence, Rossini’s “Armida” is built with a rather autonomous musical language, stirred by Romantic influences that are quite distant from the manner (and mannerisms) of past musicians. And it is this very Romanticism that is responsible for Rossini’s loss of his theatrical sensibility, but it is also thanks to this Romantic drive that we are able to discover the source of the wonderful pages in the opera (e.g., first-act duet), as well as a new intelligence in the instrumentation that leads to bold amalgams and to genuine orchestral inversions. The latter are already evident in the overture.

But if these are the grounds for the shortcomings we have found in “Armida”, it is furthermore impossible to state that nowadays this work is still easy to hear or watch. In the context of a festival like the “Maggio Musicale” — which is essentially a cultural event — historical revivals are certainly allowed, perhaps also expected, undoubtedly useful. But if we believe that opera lives and can only survive inasmuch as it provides enjoyment to the public, then we must prevent this work from joining the repertory of regular seasons. The felicitous interludes are not enough to justify the spectator’s patience during the seventy minutes of the first act, in which, furthermore, one has to watch the awkward bustling about of characters thrown on the stage without the necessary mutual dramatic communication. Nor can we adhere to this work’s most authoritative exegeses, which claim to see in it the triumph of voluptuous love in a sensual and rousing atmosphere. The second act certainly tends in this direction, thus revealing the true intention of this score.

Rossini’s art expresses itself in “Armida” with its prodigious ability to expand the sentiments. Yet, one must acknowledge that artifice and scheme too often peep out of the screen of the rare brilliant passages.

This evening’s performance unfolded smoothly and suitably enough. It is worth noting the musical direction of Tullio Serafin, as well as the voices of Maria Meneghini Callas, Francesco Albanese, Mario Filippeschi and many others. On the other hand, Bozzetti’s stage direction and Alberto Savinio’s sets and costumes were disappointing. It’s about time that one stopped securing at every turn the services of one or the other of these two venomous brothers. The bad taste of this decadent family is in the process of invading too many fields: after his paintings, the sceneries of De Chirico; the articles in the “Corriere della Sera”; the music and sceneries of Savinio. The fripperies of one influence the other and vice versa in a continuous crescendo.

Thus, Rossini’s “Armida” was sadly accorded such a production, laden with useless details, gigantic lightning bolts and fanciful stage effects. Savinio certainly dominated this evening’s spectacle, doing further harm, but more to himself than to the audience.

Reports of the evening noted the presence in the theater of the Minister of the Interior, the diplomatic representatives from various countries, and a very elegant audience. At intermission, from the upper foyer, the “lesser” audience members enviously gawked at the pompous parade of Florence’s luxuriously attired high society. And this, too, was a most dispiriting spectacle.Luigi Pestalozza

(Translation by Jim Legnani)

Oggi

May 8, 1952

(courtesy of Cosimo Capanni)

Rossini having a showdown with Armida’s charms

After the performance of the opera by the composer from Pesaro, the “Maggio” presented Frazzi’s “Don Quichotte”

Review by Teodoro CelliFlorence, April

The marvelous audience that packed the Teatro Comunale in Florence on the April 26th inaugural performance of the XV Maggio Musicale Fiorentino laughed only once in the whole evening, but they laughed heartily. This might surprise most readers who know that the opening opera was Armida by Gioachino Rossini; we say surprise because for most Italians, Rossini is exclusively, so to speak, the author of the very funny Barbiere. The scarcity or even absence of performances of the rest of Rossini’s works, and our consequent ignorance, did and still continues to do injustice to the composer from Pesaro by disregarding his serious, semi-serious, and tragic operas. Guglielmo Tell is barely remembered, but the fact that, among the twenty-one operas written between Barbiere (1816) and Tell (1829), fifteen belong to the “seria” genre is not taken into account. One might say that this year’s Florence May Festival, with most of the evenings devoted to a Rossinian profile, is focused more on the “serious” rather than the “comic” Rossini. And Armida, the inaugural performance, is not only consistently “serious” and dramatic, but also shows Rossini having a showdown with this unusual, bizarre, fantastic, chivalrous and mythical libretto in hand.

The main attraction and greatest interest of the opening evening was precisely to see how the composer managed to treat such a subject musically. The audience did not laugh because there was nothing to laugh at, and the only laughter heard, as mentioned earlier, was a result of a mere incident. In the last Act, two knights are heading for the enchanted garden of the sorceress Armida in an attempt to make the seduced Rinaldo hear the call to duty. Their succeed in their intention and are about to take Rinaldo away from the magic when Armida, imploring and threatening, comes in to defend the rights of her love. At that moment, one of the moralistic knights cries out to Rinaldo: “Do not yield!” As this happens during a banal recitative, the total lack of musical accompaniment and the unfortunate vocal inflection of the interpreter suddenly brought into light the absolute nonsense of the ridiculous libretto. As a consequence of this naïve stage situation, the audience had the pleasure to burst into laughter.

As for the rest of the evening, the audience seemed really interested, even beyond the cultural context of the event; they enjoyed a good performance of a score of extraordinary difficulty (singing the Second Act’s “aria con variazioni,” Maria Meneghini Callas actually had to and, in fact, did perform true miracles with her voice). The audience felt special sympathy for the naiveté and considerable honesty with which Rossini approached the fable-like subject of the libretto. Armida is not a masterpiece, not even an essential opera. However, it may help to erode the widely held belief that Rossini had no “sensibility for the fantastic” (actually, La Cenerentola could also serve this purpose, if approached appropriately). The story of Armida has very few elements of theater: in the First Act, Armida approaches the field of the Christian crusaders in order to seduce Rinaldo, the knight with whom she is in love; in the Second Act, she takes him to an enchanted forest with her; during the Third Act, Rinaldo is freed from the sorceress’ trap by two companions; defeated and sorrowful, she falls into despair and magic invocation of revenge. But with these few elements, Rossini has managed to convey, if not often then at least intermittently, a true sense of the supernatural and the fantastic. Armida was composed in 1817, at the time when Rossini was at the climax of his infatuation with Isabella Colbran, the singer who would become his first wife. Echoes of this love can be perceived in Armida’s part, the only well defined character of the opera: a sonic symbol of sensuous enchantment can be recognized in the sorceress’ vocalism. The arrival of Rinaldo and Armida at the enchanted forest is marvelous for the mysterious atmosphere it conveys (Rinaldo’s dreamy “Dove sono io?”); Armida’s final imprecations, impetuous and dramatic, are marvelous as well. In this, as in many other previous moments, the too often forgotten dramatic Rossini is revealed – the Rossini that inspired Donizetti, Bellini and Verdi. Even Riccardo Bacchelli, an expert on Rossini’s operas, has admitted that he did not recognize before the rehearsals the force and dramatic greatness of the sumptuous and sensuous Armida.Teodoro Celli